HISTORY

We are updating this page, so that the history is not yet fully completed but, if you have any suggestions or have any questions about the history of Eryholme, please contact us via the website contact form and we will respond as soon as we can.

As mentioned on the home page, a comprehensive and fully illustrated history of the village has been written by Professor A J Pollard, and published in 2019 by Fonthill Media. The following is largely a summary of its contents, plus some recent additional research and rethinking on his part.

‘This estate is a perfect paradise, the Tees river, fine woods, beautiful prospects, rich land, pretty farm houses, everything conspires to adorn it’. So wrote Elizabeth Montague in 1775, one of the first ‘bluestockings’ and lady of the manor of Eryholme at the time. And so, its residents would affirm, it has remained so until the present day.

Eryholme is situated in the central Tees Valley, in the far north of the county of North Yorkshire (formerly the North Riding) with its northern and eastern boundary formed by the river. Its centre consists of a few houses, with farms scattered over an area of about 2,200 acres and its height above sea-level rises from 25 to 60 metres. It is coterminus with the parish boundary, the civil township (settlement) and one manor/lordship, and its population has rarely altered, being at its highest at about 200 in 1300.

For items printed in bold, see under the Additional Information tab for an extended description. There is also a list of inhabitants from 1399 for those doing family research. For possible further information on individuals please contact Tony Pollard via the website contact site.

THE MIDDLE AGES, 1066-1499

From the patchy and scarce evidence, it is clear that there has been considerable continuity over the centuries , but also great change. For two centuries since 1066 Eryholme grew and prospered. After 1300, for various reasons, it shrank considerably and could well have ended up as one of England’s many ‘lost villages’. However, although the character of its agriculture changed, from about 1600 the nature of the settlement hardly altered until the twentieth century.

Its name derives from the Scandinavian root words ‘aergi’ and ‘holme’. The latter means a low-lying loop in the river which is subject to flooding, as it is still today. ‘Aergi’ could either mean a summer pasture or somewhere cattle are reared and grazed.

There are no signs of its being a Romano-British settlement, as in nearby Dalton and Hurworth, nor Anglo-Saxon, and it is difficult to say when Eryholme actually did become established. Its first known lord was Lady Godiva’s godson and it belonged to Earl Edwin of Mercia in 1066, being recorded as ‘Erghum’ in the Domesday Survey of 1086. It then passed to the Earl of Richmond and was held by his knight, Tenay, by 1140. He and his family remained lords of the manor until about 1286 when it passed to Richard de Romanby. Between 1301 and 1327 it was acquired by the Markenfields of Markenfield Hall, whose descendants remained until 1570. However, hardly any of the families were resident in the village during this period.

After 1100 the village was probably clustered around the manor and church and its ford had been in use for some time, as appears from the legend that St Cuthbert’s body was carried across the Tees in 995 on its way from Ripon to Durham.

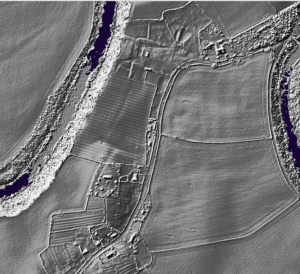

Its farming came to concentrate on arable, typical of the Medieval open field system and there are surviving ridge and furrow still visible (see also the Archaeological Survey under the Additional Information tab.

. Medieval house platforms below the churchyard

Medieval house platforms below the churchyard

February 2025, with ridge and furrow clearly visible and church in the trees in the background.

February 2025, with ridge and furrow clearly visible and church in the trees in the background.

The fields were communally worked and the lord kept a proportion for himself, with the tenants having to work one or two days a week on his demesne, plus extra at harvest. More and more land was put down to arable during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, accompanied by a rise in population, signs of the increasing prosperity evident in much of the rest of England. This is also shown in the building of the stone church around 1200 (see under History of the Church). A tax return of 1301 revealed that Eryholme was thriving and indeed was the wealthiest settlement on the south bank of the Tees apart from Yarm. Pollard estimates that its population was the highest it has ever been, being well over 200 and the inhabitants ranged from the lord of the manor to prosperous freeholders and tenants, employing labourers themselves, as well as craftsmen such as a carpenter and smith.

Disaster struck in 1319 when Eryholme was raided and sacked by the Scots. The restoration of the church in 1889 revealed evidence of fire and it is likely that many buildings, including the manor, would have been burnt to the ground. This coincided with a series of failed harvests and livestock epidemics and the result of these catastrophic affects can be seen in the much diminished tax returns. Even if there were signs of recovery, the Black Death in 1349 resulted in a decrease in population in the area of up to 50 percent and it has never really recovered to the present day, remaining around 60 to 80. Much of the settlement was abandoned, evidenced by the still visible earthworks between the Old Vicarage and the Old School House.

However, unlike many villages (for example, locally, High Worsall, Low Dinsdale and Sockburn), Eryholme survived. One reason may have been proximity to the crossing of the river Tees, by ford and ferry, on one of the branches of what came to be called the Great North Road, being much used by everyone from kings downwards.

As elsewhere, by the end of the fifteenth century, the decline in population and consequent shortage of labour made it impossible to maintain the old open field system leading to enclosure by agreement in 1499, the creation of separate farms and the conversion of land to pasture to meet a growing demand for wool and meat.

With enclosure came the building of farmhouses on the new larger farms and the abandonment of the existing farmhouses in the village, leaving a few labourers’ cottages. By the end of the sixteenth century and during the seventeenth century the present Eryholme Grange was built, followed by Break House, Carlingholme, Low Hail, the Holmes and Low Holmes, all of whom have survived in some form.

The present pattern of settlement was thus established over four hundred years ago and has hardly changed since.

DIVISION, REBELLION AND CIVIL WAR, 1499-1714

By the end of the 15th century the population had recovered to about 150 and then remained stable, despite a steady flow of emigration seeking work elsewhere, as well as a high death rate at birth and frequent plagues.

By this time also there were several prosperous farmers, as seen from the valuable possessions written in their wills (see additional information in due course). Many local families intermarried and remained as tenants for several generations, increasing the size of their houses and leaving valuable possessions. Others married further afield in the wider Tees Valley, some reaching gentry status. Darlington was the nearest market where their main commercial and business was focussed, and their other responsibilities were to enforce the law and maintain the part of the king’s highway from Entercommon to the ford, which was considered a communal and philanthropic duty.

The poor suffered however and were helped out by various bequests. Being on the main road, there were a number of vagrants passing through the village. In May 1597, for example, ‘a stranger was found dead in Wood Gill’ and in July of that year an unknown poor woman was buried having died in ‘Vincent Freer’s street’.

Most remained loyal to the Catholic church until after the Rising of the Northern Earls, when many nobles in the north rose up against Elizabeth 1 and her Protestant regime. Many took part locally but no one in Eryholme was hanged as a result and the first fully Protestant priest arrived in 1576, when Protestantism was probably finally accepted by most of the village.

TO BE CONTINUED